Microtiming Deviations and Swing Feel in Jazz

Does it swing?

"It Don't Mean a Thing, If It Ain't Got That Swing" is what Duke Ellington and Irving Mills claimed already in their well-known 1931 Jazz Standard to emphasize the role of the Swing Feel for Jazz. But what actually makes a jazz performance swing?

In an experimental online study, a research group of the Max Planck Institute for Dynamics and Self-Organization and the Georg Elias Müller Institute for Psychology in Göttingen has scrutinized the phenomenon. Our focus was on very small temporal fluctuations in rhythm (microtiming deviations) and their influence on the Swing Feel.

In a first step we recorded well-known jazz pieces played by a professional jazz musician. Then we examined the pianist's microtiming deviations and systematically changed them. In a second step we presented the original and modified versions of the pieces to professional and amateur musicians (with a jazz or a classical background) and had the pieces evaluated according to how natural and technically correct they sound and how much they are swinging.

Background and motivation

Jazz music often evokes a pleasant feeling in listeners and the desire to move to the music, e.g. to tap one's feet or to nod one's head. In addition to this phenomenon known as "groove", jazz musicians have known the phenomenon of "swing" since the 1930s - not only as a style, but also as a rhythmic phenomenon. For a long time it appeared difficult to characterize it in detail, e.g. Bill Treadwell wrote in his introduction "What is Swing": "You can feel it, but you just can't explain it". Musicians and many music fans nevertheless have an intuitive feeling for what swing is. But thus far, musicologists have unequivocally characterized only one rather obvious feature: Successive eighth notes are not played for the same length of time, but the first one is played a little longer and the second (the swing note) a little shorter. It is known, for example, that the "swing ratio", i.e. the length ratio of these notes, often takes on a value close to 2:1 and tends to become smaller at higher tempos and larger at lower tempos.

In addition, the role of rhythmic fluctuations has also been discussed. For example, sometimes one can hear soloists playing distinctly "after the beat" for a short time, or in a "laid-back" fashion. But is this necessary for the swing feel, and what role do much smaller deviations (microtiming deviations) play that are not consciously perceived? Musicologists such as Keil and Prögler have long held the opinion that very small temporal deviations, e.g. between the various instruments, are substantial in order to make a jazz performance swing, but this has been discussed controversially in recent years. If jazz musicians can feel it, but not explain it precisely, we should be able to characterize the role of microtiming deviations operationally by having experienced jazz musicians evaluate recordings with original and systematically manipulated timing.

Our approach

1. Recording of pieces

We recorded twelve pieces (all jazz standards) played by a professional pianist on a MIDI keyboard. While he was playing, he heard a quantized track with bass and drums via headphones (without microtiming deviations), which not only provided the accompaniment, but also took on the function of a metronome.

2. Systematic manipulation of the recordings

The manipulation of the recordings was done in several steps. Since the piano was recorded digitally, the onset and duration of a played note as well as its loudness were recorded and could also be altered digitally.

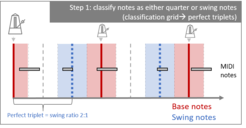

First, however, all notes had to be classified (i.e. which note extends over the first two of three triplets (i.e. the "base note") and which one represents the last triplet (or "swing note")).

What does Swing Ratio mean in detail? (click here)

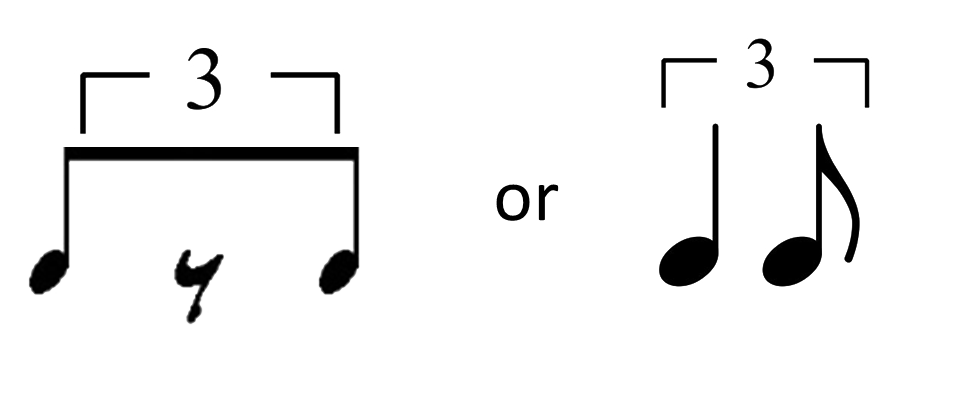

The swing ratio is the ratio of the performed length of successive eighth notes. In straight feel (as we know it from classical music for example), the eighth notes are played equally long. The swing ratio is then 1:1.

It is important to note that the length is not the actual duration of the sound, but only indicates when the next note begins. So it doesn't matter if the note is played short or long. With a swing ratio of 2:1 (perfect triplet) the first eighth note would last twice as long as the second. The middle note of the triplet is usually not played separately, but connected to the first note or replaced by a pause. This can be written as follows:

In jazz performances, swing ratios are neither perfectly constant throughout a piece, nor are they necessarily exactly 2:1, but they can be softer (<2:1) or harder (>2:1) depending on preference. In addition, the onset of the first eighth note does not have to be perfectly on the beat but can come a little earlier or a little later.

To classify the notes of our pianist we took the quantized track with bass and drums as reference. Since the swing ratio of the track was exactly 2:1 (perfect triplets), all notes were classified according to their proximity to this grid (see figure below). The notes were not shifted so far, but only categorized.

Determination of the average swing ratio

The average swing ratio for each piece was now calculated on the basis of the temporal position of the swing notes. For example, the recording of "So What" had an average swing ratio of 1.57:1, while the recording of "Don't Get Around Much Anymore" had an average swing ratio of 2.11:1.

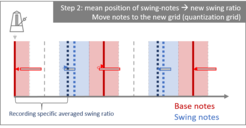

Based on the calculated average swing ratio for each piece, a new grid (quantization grid with this swing ratio) was created for the manipulation of the microtiming deviations.

Microtiming Deviations are the deviation of each individual note from a defined grid, in our case from the piece-specific quantization grid.

Manipulation of the microtiming deviations

Each piece was then manipulated in three different ways: The microtiming deviations were ...

- quantized, i.e. all variations of the note onsets were deleted and the notes were shifted to a fixed quantization grid. (see figure below)

- doubled, i.e. the distances from the fixed grid were doubled (i.e. the microtiming deviations were made twice as large). For example: If in the original version a swing note was played 3 milliseconds before the average swing note of the piece, in the manipulated version it was shifted to 6 milliseconds before the average swing note.

- inverted, i.e. the microtiming deviations underwent a sign change, but kept the same distance from the fixed grid as in the original. If e.g. in the original version a swing note was played 3 milliseconds before the average swing note of the piece, then in the inverted version it was played 3 milliseconds after the average swing note.

Schematic representation of quantization:

The new quantization grid exhibits the average swing ratio for the respective piece as the new (constant) swing ratio (dark blue dotted line). In this example, the swing ratio is smaller (i.e. < 2:1) than in the classification grid (light blue dotted line).

Since musicians rarely play exactly the same swing ratio throughout a piece, there are usually small deviations from the average swing ratio.

During quantization, all note onsets are shifted to the new quantization grid. This determines the onsets of each note in each bar and the swing ratio becomes constant from the beginning to the end of the piece. The duration and loudness have not been changed.

For each piece and for each manipulation, we determined different measures of the rhythm, e.g. the average swing ratio, the average deviation from the average swing ratio (how much individual notes vary), the tempo, etc.

3. Experimental online study

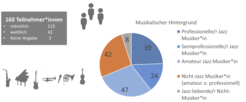

The three manipulations and the original recording constituted the four versions for each jazz piece, that we wanted to test. For this purpose we created an online listening study and invited musicians with different backgrounds and expertise to participate (see figure). Each participant listened to all twelve pieces, but it was decided randomly, which version of the piece they would listen to. After listening to a piece they were asked to rate how natural it sounded, whether it was played technically correct, and how much it was swinging.

Results of the online study

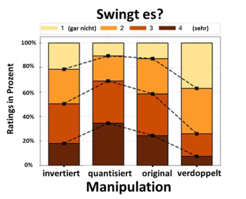

Throughout all the pieces, the quantized versions got slightly higher swing ratings than the original recordings and the inverted versions were rated almost the same as the original versions. Only in two pieces were the inverted versions significantly rated as less swinging. In contrast, doubling the microtiming deviations always led to significantly lower swing ratings.

Comparing different pieces, we find that they got different swing ratings (regardless of the version presented). So it seems that there are more influencing factors other than microtiming deviations. Interactions with other influencing factors are also possible. The groups of participants also differed in their evaluation. Professional jazz musicians generally gave slightly lower swing ratings - regardless of the piece and version - and thus were more stringent. But all groups of musicians gave their ratings in the following order

quantized > original & inverted > doubled

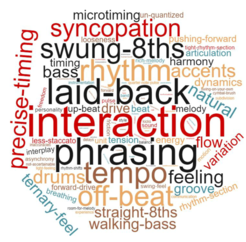

What makes a piece swing? Answers of our participants

At the end of the online survey we asked our participants, which features they thought made a piece swing. We summarized their answers in keywords in such a way that frequently mentioned features are shown in a larger size. This suggests that rhythm plays a major role, but other factors may be important as well.